Behind the scenes of SDSU: History of ethanol plant revealed

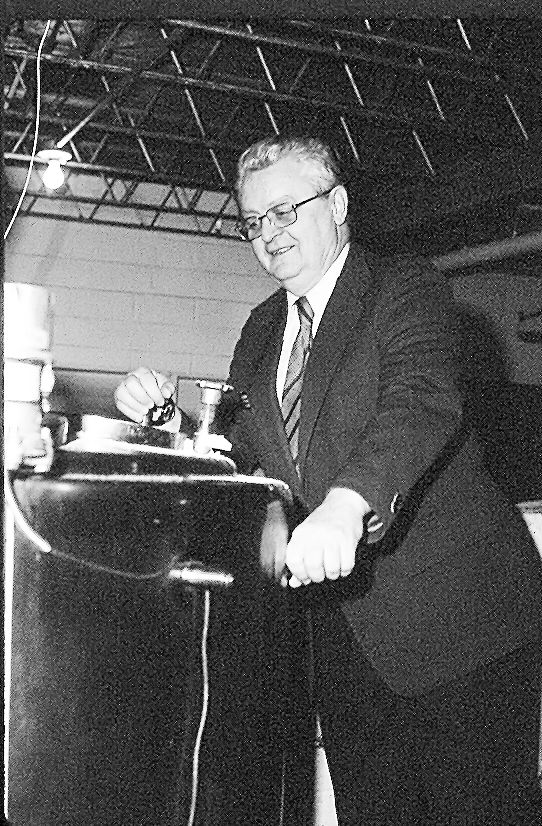

Dr. Middaugh was the man that came up with the plan to start using corn to produce ethonal as a fuel source in the late 1970s. His plant operated on the SDSU campus from 1978 until 1987.

October 7, 2015

South Dakota State University has an interesting secret, one that the university wants to make better known.

During the late 1970s and most of the 1980s, SDSU housed a farm-scale ethanol plant. The plant was the first of its kind in the United States according to Bill Gibbons, the industrial microbiologist for the microbiology department.

The idea of an ethanol plant came from Dr. Paul Middaugh, the industrial microbiologist for the microbiology department at the time. His idea stemmed from an excessive amount of corn grain and high oil prices. Middaugh’s plan was to turn the extra corn into ethanol, and then turn that ethanol into a cheaper fuel source. The idea was not a new idea since Henry Ford initially designed his engine to use ethanol and gasoline eventually replaced it.

“His [Middaugh’s] initial thought was actually using biomass; so crop residues, wheat straw, corn stover, wood by-products, municipal solid waste and converting that into ethanol… But because it’s harder to break cellulose down into the simple sugar glucose, while we were developing that technology, he at the same time was saying, ‘Well let’s take all that abundant corn we have got and that’s easy to break down. You know people have been producing whiskey and beer and everything else… let’s produce ethanol as a fuel,’” Gibbons said.

Middaugh began collecting materials needed for the project, such as 1,500-gallon steel tanks, a distillation column that was made by one of his students and the student’s brother near Sheldon, Iowa, commercial enzymes and ground corn, and finding a useable space in 1976, according to Gibbons. It took about two years for all the materials to be collected and operation began in 1978 inside the Physiology Lab located near the Alfred Dairy Science Hall.

Gibbons said for the first part of the project’s history, it was mainly used for demonstrations. One day each week the plant hosted open houses in which visitors could come tour the plant to see how the ethanol was being made.

According to Gibbons, some of the most memorable visitors included South Dakota Representative Tom Daschle and New York Representative Geraldine Ferrar. Daschle pushed the USDA to give the project $250,000 worth of funding. On one occasion, the columns were put on a flatbed trailer and taken to Washington, D.C., where plant operators performed a demonstration that drew the attention of many politicians, political aides and passers-by.

After 1980, different departments on campus used the plant for research purposes. Some of the research topics were related to the overall ethanol plant project, but others were related to the production process used in the plant, and the by-products that came from the production of ethanol.

“It brought a lot of people doing research in different departments together… We had plant science people. We had ag engineers, mechanical engineers, dairy science, animal science, economics, microbiology. You know, there were at least seven or eight departments and faculty, grad students and undergrad students from those departments all working together on a really big project,” Gibbons said.

Gibbons worked directly with one of the many research projects that took place at the plant. He said he worked on testing different aspects of the conversion process. Many aspects he tested or similar variations of the aspects tested at the plant are still in use today. Engineering students worked on projects to determine how much energy was required to distill the ethanol; members of the animal science department looked at the feeding value of the dried distillers grain, which is a by-product of the production of ethanol; agricultural engineers worked on modifying engines to see if it was possible to use the straight ethanol to fuel them rather than having to take all of the water out of it before mixing it with gasoline and a group from the economics department studied the feasibility of producing ethanol on the farm-scale, in which individual farmers produce the ethanol right on their own farms.

Gibbons stated that the ethanol plant on campus was really the starting point for the industry as it is known today. The SDSU plant was the first to use the dry-milling process where they ground dry corn and added water to it after milling it. The only other company that was producing ethanol for fuel use at that time was Archer Daniels Midland. ADM was doing a wet-milling process in which they ground wet corn to make ethanol. Gibbons said that ADM started around the same time as the plant at SDSU did.

“As soon as we started doing this the reason that you had plants going up in Scotland [S.D.] and Sherman [S.D.] and every place else was these farmers were saying, ‘you know we are losing money selling corn. If we convert our corn into ethanol, we can sell the ethanol and then we have got the distillers grain to feed, and we can make money on that,’” Gibbons said.

From the research done at the plant on campus, researchers determined that farm-scale ethanol production is not feasible. Even though the small-scale production was not feasible, many aspects of today’s ethanol production were tested in the plant. With the information gathered in the original plant, many large-scale ethanol plants were started including plants in Scotland, S.D., Sherman, S.D. and Sheldon, Iowa.

The Physiology Lab building that housed the on-campus ethanol plant is still standing. After the ethanol plant went out of operation, there was research done on mushroom production for about five years, according to Gibbons. Now the building is used for computer repairs and storage.