Hundreds of emails compromised in spam frenzy

The newest way the department has helped students and faculty recognize and report email scams is through a MyState or InsideState form. Just within three days the information was viewed more than 1,300 times.

April 26, 2017

Email notifications popped up on Grace Dahlman’s phone one after the other Thursday night.

Hundreds were coming in within a minute. They quickly reached the thousands.

It got so bad she turned off email notifications on her phone.

She’d been hacked.

Dahlman, a senior hospitality management major, was one of hundreds of students whose accounts were compromised last week. Just a few days after the first account was compromised, 250 accounts were added to the list.

Ronnie Straub, IT Services manager, can recall exactly where he was when he was notified the first account had been compromised.

“It was 7:25 p.m. on Tuesday,” Straub said. He’d been sitting down with his children eating an evening snack.

But when Straub received an email from a compromised account he sprang into action, working to stifle the pandemonium that might ensue if it wasn’t caught quick enough.

He contacted people within his department to keep it from spreading and contacted Weebly, which hosted the spam site, to disable the site and account. It was down by 10 p.m.

“It’s an exponential event. So if I got compromised, everyone in my contact list it would send out too, and if they fell for it, it would go to their contact list. It would go to five, ten, a hundred people within two hours,” Straub said.

Compromised accounts are common — Straub said IT Services handles compromised email accounts daily. But having this amount at one time is unprecedented.

The spam emails, or phishing emails to imply someone “fishing for accounts,” are starting to get under control now, Straub said. But it’s a continuous problem.

“It’s a cat and mouse game. We have smart people battling smart bad guys, and they’re adapting. The proof that it won’t go away is that they’re adapting,” Straub said.

For example, IT Services blocked emails that had hyperlinks to certain sites within the email body, but spammers got around it by attaching a PDF that included a hyperlink.

But the frenzy helped IT Services realize staff members need to increase efforts on email literacy and how to identify fake emails.

“This really pushed us to the next step,” Straub said.

Dahlman said she received an email from an SDSU account with a subject line for a Jacks email update.

“It looked legit, that’s why I believed it,” Dahlman said.

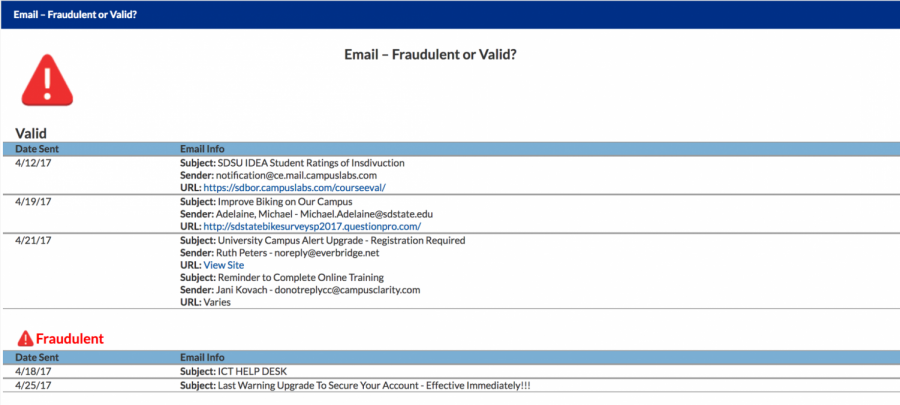

But the emails that spread across the university’s email network had multiple red flags, according to Straub.

Some warning signs included that some of these emails were sent from SDSU students about subjects that wouldn’t apply to them, email’s started off with “Dear email users,” switched to a PDF from the original email file, or didn’t include any phone numbers on the email.

Warning signs included that some of these emails were sent from SDSU students about subjects that wouldn’t apply to them, started off the email with “Dear email users,” switched to a PDF from the original email file or didn’t include any phone numbers on the email.

“If I send out an email from the help desk it’s going to be a lot more friendly,” Straub said.

An even bigger indicator that the email is fake is the website URL that’s revealed when a computer mouse hovers over the hyperlink. All official SDSU emails will go to SDState.edu. The spam emails that many students’ emails were flooded with went to Weebly.

Straub plans to include an informational packet in the New Student Orientation sessions this summer. So far the department has released information to handle spam attacks on its Twitter and Facebook pages.

The newest way the department has helped students and faculty recognize and report email scams is through a MyState or InsideState form. Just within three days the information was viewed more than 1,300 times.

Dahlman emailed Michael Adelaine, vice president for technology and safety, after she realized her account had been compromised. She was directed to the support desk and reset her password.

She doesn’t want the same experience to happen again, and hopes other students will learn how to identify fake emails as well.

“Be aware of what you’re clicking on when you’re opening emails,” Dahlman said. “If it does happen, like you get spammed, just figure out who to contact to fix the situation.”