The real story of Thanksgiving

November 16, 2021

This year, we celebrate the 400th anniversary of what we consider the first Thanksgiving. Many of us remember being taught about the first Thanksgiving in grade school. Perhaps we donned costumes for a Thanksgiving pageant or recreated the scene with construction paper, being sure to add a colorful turkey.

But more than likely, we weren’t told the full story of what happened at that celebration feast, and there are many misconceptions surrounding the real story of Thanksgiving. The following information comes from SDSU history professor Charles Vollan and staff members at the Plimoth Patuxet Museum in Plymouth, Massachusetts.

Before the feast

First, this was not the first time a feast of Thanksgiving had occurred. Most cultures around the world have traditions of celebrating at the end of harvest season, and sometimes that meant having a feast or fasting in prayer.

Second, many people wrongfully believe this was a “first-contact” event between the Natives and the Europeans. For over a hundred years prior to what we consider the first Thanksgiving, the Native people of what would become New England had many encounters with Europeans—and with those encounters came disease.

From 1616-1619 there was a smallpox epidemic with over a 90% fatality rate that ran rampant through the Patuxet tribe, which was a subgroup of the Wampanoag tribe.

A Patuxet named Squanto (or Tisquantum) was captured during a Spanish raid in 1614 and spent years in England where he learned English. When he was finally freed, he found he was the last living member of the Patuxets as all other members of his tribe had died.

Squanto joined the main Wampanoag tribe upon his return to America, and it would be the Wampanoags who feasted with the Pilgrims in 1621. Squanto later became a sort of translator between the Wampanoags and the Pilgrims, who arrived by Mayflower in Plymouth Harbor Dec. 16, 1620.

A peaceful affair—or was it?

Massosoit (or Ousamequin) was an important leader of the Wampanoags at the time, and he wanted protection against the Narragansetts, an enemy tribe. The Narragansetts now had far greater numbers than the Wampanoags, so it made sense for Massosoit to want to make allies with the English. However, some members of the tribe didn’t like the idea.

It’s also important to note that the Native people didn’t recognize personal ownership of land, but they knew where their land started and ended. So while the Wampanoags may have thought they were only letting the Pilgrims use the land, the Pilgrims would have thought they were given it.

The Pilgrims were also wary of the Natives, but to seek peace they created a treaty in March that marked their temporary alliance. They were allies with reasons to distrust one another, so it’s likely there was a level of tension at the harvest celebration.

It was also a three-day celebration. Ninety Wampanoag members joined the Pilgrims, and instead of the “traditional” turkey feast, everyone dined on deer meat—so no mashed potatoes, no pumpkin pie. Local vegetables and fish, however, were likely present at the dinner table.

This would have occurred between Sept. 21 and Nov. 9, 1621, and after that, the celebration wasn’t really talked about until the 19th Century.

The modern Thanksgiving

In 1789, President George Washington declared a national day of thanks, thanking God for the newfound independence of the country.

President Abraham Lincoln later made a proclamation in 1863 declaring Thanksgiving a national holiday, and he said it would furthermore be celebrated the last Thursday in November. This declaration came after a few successful months for the Union during the Civil War, so there were many reasons to celebrate.

This is really when the modern tradition of Thanksgiving as we know it began.

There are still a lot of details we don’t know about the first Thanksgiving. Much of the history we do have was told from the European side, and as professor Vollan said, we often don’t consider an event to be important until much later and don’t think to record what happened.

Regardless, this is a good time of year to remember to be thankful for what we have and remember the true history behind the holiday.

Other facts:

- The Pilgrims were not Puritans, nor did they dress in all black or have buckles on their shoes and hats.

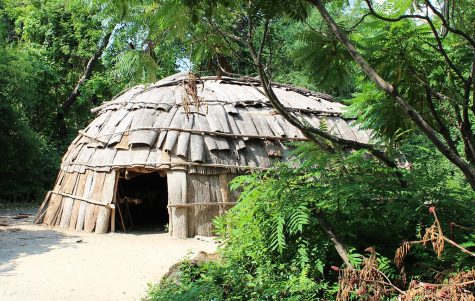

- The Wampanoags lived in Nush Wetus, which were bark-covered houses—not teepees.

- There was no turkey. As stated earlier, fresh deer would have been the main entrée for the feast.

- Today, about 4,000-5,000 Wampanoag live in New England.

- The Smithsonian Channel is releasing a new film, “Behind the Holiday: The First Thanksgiving,” Monday Nov. 22 that will include recreations filmed at the Plimoth Patuxet Museum.

- For more information from the museum, visit plimoth.org