Agriculture is becoming increasingly more high-tech. Farmers are not only improving production, but are also bettering the environment.

Through data, farmers apply the right amount of inputs of fertilizer, seed and water to achieve high production yields.

Environmentally, this is a win, said Bill Gibbons, interim associate dean for research in the College of Agriculture and Biological Sciences.

“This will eliminate over-application of these inputs, and result in better soil, water and air quality,” Gibbons said.

A myriad of technologies are used in precision ag. Combines detect the differences in yields in fields while harvesting and maps reveal the structure and properties of soil like pH, nitrogen and phosphorus levels.

Using the data, GPS-guided systems steer machines to reduce seed and spray overlap or placing a specific percent of pesticide on each section of a field. Other sensor systems and drones can track field conditions as well.

“Precision ag is really like a toolbox of technologies that farmers can implement to increase their efficiency and environmental sustainability,” Gibbons said.

Researchers are also working on sensors for other nutrients and microbial activity.

David Wright, head of the agronomy, horticulture and plant science department, said precision ag became a larger field of study in the 1970s. It was primarily developed in California to assist in vegetable production.

Improving the environment was not originally the main goal during the development of precision ag, according to Wright, rather it was focused on getting the most out of crop yield. Environmental benefits were just a side effect.

“For years, farmers were concerned about the environment, but didn’t have the knowledge or experience to address it,” he said.

Precision agriculture has come a long way and has become more understandable for the industry.

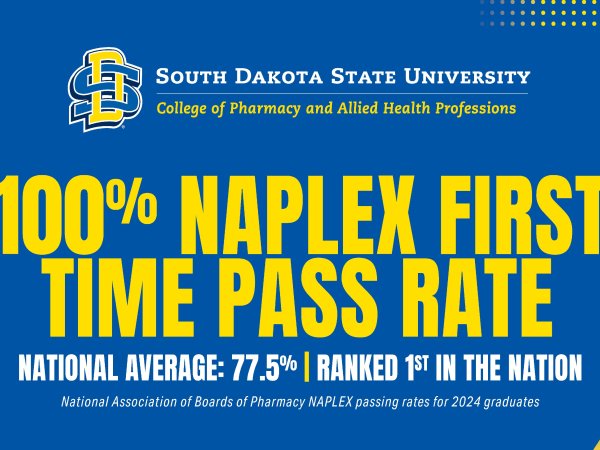

SDSU was the first school in the nation to offer a four-year precision-ag degree. There were only eight students in the major when it began in 2016, there are now 57 students majoring and 90 students minoring in the program.

Garrett Wagner is a sophomore agricultural science major with a precision agriculture minor and plans to work at a co-op after graduating. He chose his minor due to precision ag’s growing prominence in modern farming.

“Environmentally, the biggest thing with precision agriculture is reducing pollution,” Wagner said. “There is a lot going in with that to get the right amount of pesticides and plants as possible and trying to keep runoff for that low.”

As the field of study grows, the building of a specialized precision-ag facility is planned at SDSU. The building will be the first of its kind in the nation. Wright hopes it will not only help farmers in the United States, but across the world.

According to Gibbons, the facility will create an “innovation ecosystem” and bring together research from the departments of agronomy, horticulture and plant science to enhance scientific research and teaching in the field.

“What we teach in the precision ag facility will be based off the research we will conduct,” Wright said.

The facility project was signed off by Gov. Dennis Daugaard in March, but there is no projected completion date. It will be located north of the Dairy Bar and south of the Animal Science Complex.