Hobo Day started as few long-standing traditions do — the first Hobo Day was a failure.

R. Adams Dutcher witnessed the failed event at the University of Missouri when he was a student at South Dakota State University.

“The event failed there because too many actual hobos showed up for the event, and it scared off the college students,” said South Dakota State Archivist Crystal Gamradt in a February presentation on the history of Hobo Day.

Dutcher brought Hobo Day to SDSU in 1912 and the school has celebrated it every year since, except in 1942 when it was canceled due to World War II.

Although some traditions are roughly the same, controversy has sparked many changes to the 105-year-old tradition over time.

One notable change has been with the parade. Although students still build floats, the sizes have shrunk considerably.

“By the 1960s, the floats could be described as enormous and spectacular,” Gamradt said. “Due to safety concerns and collapsing floats — due to their enormous size — floats began to be built smaller, into more manageable portions by the 1970s.”

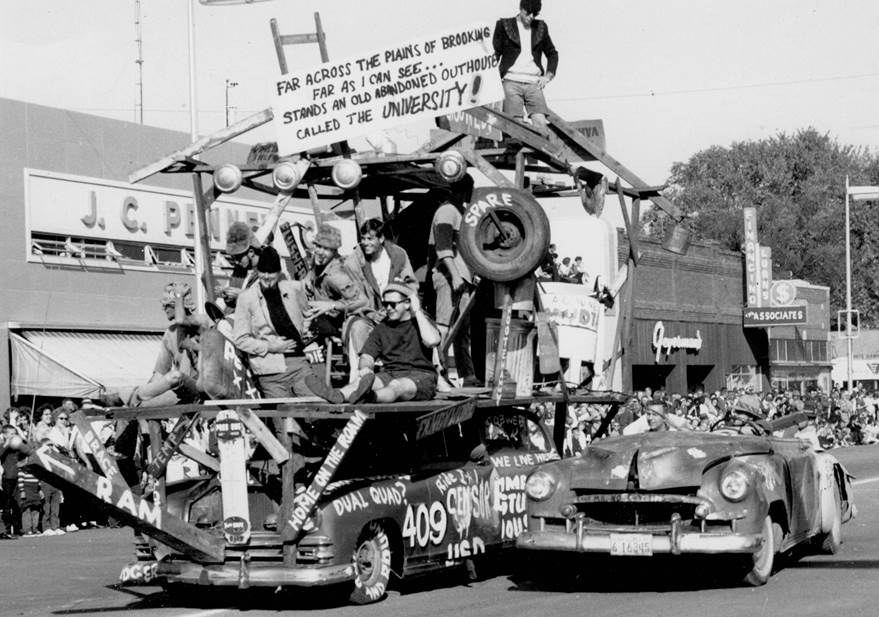

One float from 1963 referencing long-time rival the University of South Dakota caused a “sharp decline” in float building.

The float was a ramshackle mess of boards atop a painted car. There was an outhouse on the back and a sign on top that read “far across the plains of Brookings, far as I can see … stands an old abandoned outhouse called the University!”

Several newspapers declared SDSU students were vulgar and university officials decided to tone down the floats.

Along with the changing parade, many of the past Hobo Day traditions could be seen as offensive according to today’s political climate. In the distant history of Hobo Day, women would dress up as “fair Indian maidens.”

Two women dress like Native Americans during Hobo Day (1914).

Most recently, some deemed the very idea of having a Hobo Day offensive.

In 2015, a high school in West Virginia decided to have its own Hobo Day celebration, resulting in a Maryland newspaper editorial calling it “inappropriate.” A group called Covenant House, a drop-in center for the homeless of West Virginia, found the idea of Hobo Day offensive as well.

“There’s an acceptance that it’s OK to make fun of people and to talk in inappropriate ways [about the homeless] in ways we no longer talk about people of other ethnicities and LGBT people,” said Ellen Allen, executive director of Covenant House, according to an article by ESPN 99.1. “There’s a political correctness that doesn’t exist with people of poverty.”

Grand Pooba Anna Chicoine said she’s aware some people take issue with the tradition, but hopes Hobo Day 2017 will help dispel those negative attitudes, which she said come from a “base-level misunderstanding of what a hobo is.”

“After the Civil War, when the soldiers would start working their way home, they hopped on the trains and whenever the train stopped, they would stop and work whatever jobs they could find. That lifestyle really took off,” Chicoine said. “Soldiers realized that they really enjoyed that life of adventure and the thrill of it, and all the memories that they were making and the things they could find along the way.”

Chicoine said the main belief of the original hobos was wherever you go, you never forget “where your roots lie.”

“I think that really relates to us as college students, because we’ve chosen to leave our homes and everything we’ve known for the past 18 or whatever years,” Chicoine said, “for a new life of adventure and a life of memories — to see where we can go from here.”