Naloxone is being supplied to buildings and residence halls throughout campus.

Naloxone, also known by its brand name Narcan, is an opioid antagonist. This means that the drug is able to stop someone experiencing an overdose on heroin, fentanyl or prescription opioids. It is administered through the nose.

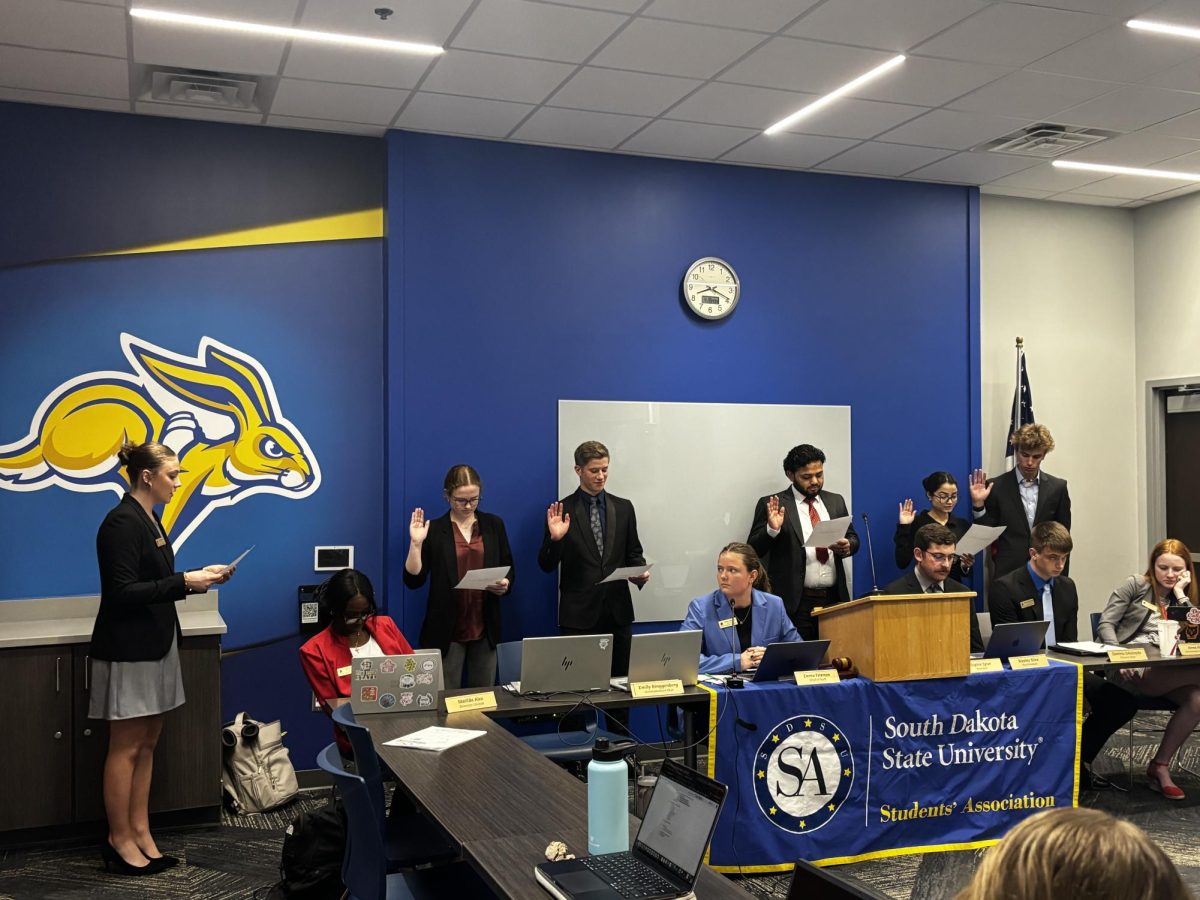

On Jan. 31, the university updated their policies and procedures portion of their website to announce that this change has been made. Then, at the Feb. 24 Students’ Association meeting, Chief of Staff Rylee Sabo announced that naloxone would be administered to buildings and faculty across campus. It is also available at the campus pharmacy.

“We have been approved to have them installed in the residence halls, Student Union, athletic facilities and the Performing Arts Center,” Sabo said.

According to Sabo, boxes were provided for free by the Department of Health.

“Boxes are placed where anyone can access them,” Sabo said.

The Environmental Health and Safety department oversees the Naloxone program and the implementation of the opioid antagonist as well as managing the ‘acquisition, distribution, transportation, storage, maintenance, training and use of Narcan at the university.’

Naloxone was first made available to employers in South Dakota under House Bill 1162, which was passed in 2023.

The bill “develops a protocol for the transport, storage, maintenance, and location of the opioid antagonist,” according to the South Dakota Department of Health website. It also “provides training and instruction, developed by the Department of Health and made available on the Department of Health website, to employees or personnel authorized to administer an opioid antagonist on the employer’s premises.”

On March 11, Gov. Larry Rhoden signed into law House Bill 1141, which works to simplify the distribution of naloxone.

Despite the overall 24% drug overdose death decrease in the United States, South Dakota is one of five states that has seen this number increase.

Angela Kennecke is the CEO of the opioid overdose prevention charity Emily’s Hope and is a news anchor at KELO-TV.

Kennecke said that other states are noticing less deaths from overdose, one of the reasons being widespread access to the free distribution of naloxone.

“South Dakota is behind in this area, but we’re working hard to change that through our efforts at Emily’s Hope.”

One of the main arguments against providing naloxone is that it enables drug use. Kennecke disagrees.

“[This criticism is] deeply misguided. Harm reduction doesn’t promote drug use. It promotes survival,” Kennecke said. “There is no evidence that providing naloxone encourages people to use drugs. What it does do is give someone a second chance and opportunity to get help, to seek treatment, to recover.”

She added that other health crises have life-saving medications accessible, whether it’s insulin for diabetes, or EpiPens for allergic reactions, and Narcan for overdoses shouldn’t be different.

“We value life,” Kennecke said. “It should be no different for substance use disorder, which is a disease, not a moral failing.”

Matthew Filteau, an assistant professor of sociology at SDSU, shares this sentiment.

“It’s widely proven that harm reduction is much more effective than abstinence-based treatment, and naloxone, commonly known as Narcan, falls underneath harm reduction,” Filteau said.

Filteau also thinks that training people how to use naloxone is important, equating proper training to knowing how to do CPR.

Sabo thinks the roll out of naloxone is a good thing.

“I think this is 100% worth it,” Sabo said. “If one of these Narcan boxes can save even one person on campus, they are absolutely worth implementing on campus.”

Kennecke and Filteau also both agree that everyone should carry naloxone.

“You never know when you might come across someone who is overdosing, it could happen anywhere,” Kennecke said. “I’ve heard real-life stories of overdoses happening in public restrooms, on city buses and even in traffic. Having naloxone on hand could mean the difference between life and death.”

Filteau said that naloxone is free in many programs across the country. He specifically mentioned Emily’s Hope and their work in making naloxone freely available in Vermilion, South Dakota.

Kennecke also believes that Naloxone should be free.

“No one should have to choose between their budget and carrying a medication that could save a life,” Kennecke said.

One of the ways that Emily’s Hope has made headway in getting this drug accessible is through their free naloxone distribution program, which supplies kits for people experiencing an overdose.

According to Kennecke, Emily’s Hope has distributed 2,836 kits, which totals to 5,672 doses of naloxone as of March 16. These kits can be found at supply boxes throughout South Dakota. There are six locations in Sioux Falls and one each in Rapid City, Vermilion and Pierre.

Kennecke wants people to know that opioid addiction doesn’t discriminate. It can happen to anyone, including your classmates, coworkers and children.

“That’s what happened to my daughter, Emily. She thought she was using heroin, but it was laced with fentanyl,” she said. “She died before we could get her into treatment. That’s why I do this work now, because no one should have to lose someone they love to something that’s truly preventable.”

Kennecke classifies substance use as a disease, not a moral failing. She says shaming pushes people further away, rather than towards the help they need.

“Harm reduction, including access to naloxone, is a compassionate, science-based approach to saving lives and offering people a path to recovery when they’re ready,” she said.