Tribal communities tackle resource shortage and isolation at home

November 4, 2020

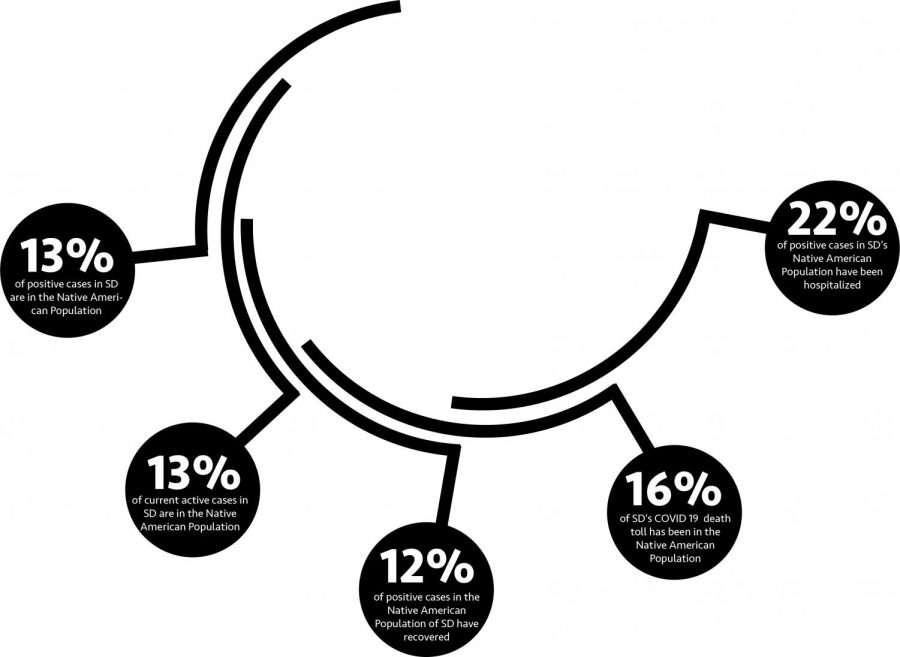

South Dakota has one of the highest percentages of Indigenous people in America, and with nine tribal communities operating under different laws from the state government, these communities faced unique challenges resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic.

Dillon Nelson is a first-year graduate student at South Dakota State University and a part of the Oglala Sioux Nation. He completed his undergraduate degree from the Oglala Community College on the Pine Ridge Reservation in January.

“There is definitely added stress from everything happening on the reservations and then coming to school here,” Nelson said. “I have to worry about my family affected by COVID-19 and me being all the way over here and not being able to help them.”

According to Erica Moore, director of the American Indian Student Center, people in tribal communities already feel the effects of isolation and food insecurity, but when a national crisis like a global pandemic or recession occurs, those factors are compounded.

“Our students are already experiencing food insecurity, lack of resources and having their communities so far from populated cities surrounding the tribal communities, so anytime we are experiencing something nationally, they’re one of the groups that are going to experience some of the more harsh impacts because they are more vulnerable,” Moore said.

Because tribal communities are independent sovereign nations, they operate under different laws than the state government. This allowed them to put in place different regulations regarding the pandemic.

Pine Ridge, along with the Cheyenne River tribe, implemented checkpoints along their borders to restrict outside traffic from the tribal community, which was supposed to prevent widespread exposure. Some communities even had curfew hours in the evening to help encourage people to stay home.

“They were trying to be very proactive in their approach to it,” Morgan Catlett-Ausborn, American Indian Academic Success adviser said in regards to the checkpoints. “It’s no fun to be 20 years old and be on lockdown all summer. But that literally meant they had to be at their house by eight at night. People may not understand why they’re doing what they’re doing, but there’s definitely a reason why they’re doing it.”

Some of the struggles students faced were inaccessibility to technology like computers and living in remote areas with no access to the internet. Nelson, who still has family residing in Pine Ridge, contributes this to a lack of resources.

“Getting resources, it seems like, is a little bit of a logistical nightmare because there’s only one grocery store in the Pine Ridge area,” Nelson said. “If there is a lockdown, people can’t go out to Walmart.”

With most tribal members having access to only one grocery store, that makes social distancing and minimal contact with others hard. Catlett-Ausborn said that a few students chose to stay in the dorms once the university went online last semester due to these limited resources.

“A lot of our students choose not to go home,” she said. “Their reservations are either on lockdown or they are worried about taking COVID-19 home to their families just because they know the situation is more dire in areas where the medical resources are not as strong.”

The AISC has been of help to students who chose to return home, though. They provided students who did not have computers, or only a single computer per household, with laptops through their lending library program. The university distributed wireless adapters or routers to students who did not have access to the internet.

Apart from support due to the pandemic, the AISC helps their Indigenous students in other ways to ensure their academic success at SDSU.

“The center as a whole is a support service,” Moore said. “They have free printing services, free tutoring services and free mentoring services … We also have specific funds set aside for research that’s going to benefit our American Indian students here on campus and in the tribal communities.”